Still With the FAQs

I have not sent these prophets, yet they ran: I have not spoken to them, yet they prophesied. ~ Jeremiah 23:21

– Pert Near Everybody

Frequently Asked Questions

Question:

Why can’t God give preachers a message to preach?

Answer:

First, the question is not one of what God can or cannot do as in a question of God’s ability. He’s God. He not only can do but does do everything he is pleased to do. The question is rather one of what God has told us he will do.

Second, If a preacher has received a message from God, then that is a message outside the closed canon of written Scripture. He paints himself a prophet or apostle, who is adding to revelation.

Question:

What if a preacher says God gave him a message and all he means by that is he has had the message persistently on his mind and thinks, or hopes, that God has providentially guided him to this message for this moment?

Answer:

Then he ought to say that instead of leading people to believe he has received direct revelation from God in some form.

Question:

Why are there so many bad sermons?

Answer:

Because there are so many bad preachers.

Question:

Why is God calling so many bad preachers to preach?

Answer:

You need to go home, pour yourself a strong cup of coffee, find a nice comfortable chair in a quiet corner, and think about what you just said.

Question:

What is a call to preach?

Answer:

A call to preach is not an extraordinary experience. It is a God given desire and ability to preach joined with a thirst for knowledge, personal holiness, and humble heart of service attested among the congregation the man is joined to and is known by.

Question:

What is a bad preacher?

Answer:

How long you have? There are all sorts of bad preachers. For instance, charlatans and teachers of false doctrine are bad preachers. Hypocrites pursuing money and fame are bad preachers. These kinds of preachers are bad preachers the way wolves are bad shepherds. These are what might be called morally bad preachers and that has nothing to do with their abilities in front of a crowd, and usually those types have pretty good abilities in front of a crowd.

If we narrow this down to bad preachers relevant to bad sermons being preached, I can think of a few ways a man might be a bad preacher, but the primary reason is incompetence. A man is a bad preacher if he doesn’t know what preaching is or how to do it. A bad preacher doesn’t know the Bible, or how it works. He doesn’t know how to exegete a passage in its original contextual setting, connect it to the big picture of biblical theology, and explain and apply that passage to a congregation. He doesn’t know how to communicate clearly and have a point to the sermon.

I need to make an important distinction here. In some cases, the above incompetence is due to the fact that the man simply doesn’t have the necessary gifting to preach despite the numerous good qualities he may have. He’s a bad preacher but it’s not his fault and he shouldn’t be in pulpit ministry. In other cases, the incompetence is due to inexperience and ignorance. He doesn’t know what he doesn’t know and doesn’t know what he needs to know. He probably showed some gifting early and was shoved up front before his inexperience and ignorance could be remediated. He needs training that all preachers are supposed to receive, but far too few do.

Question:

What should a preacher do if he lacks knowledge?

Answer:

Not try to compensate for it by yelling. He should give himself fully to praying, studying, teaching, and preaching God’s word.

Question:

Shouldn’t we just accept if a man says he’s called to preach and not comment on how well or how poorly he does it?

Answer:

(Stares exegetically)

Too Legit

Bread of deceit is sweet to a man; but afterwards his mouth shall be filled with gravel.

~ Proverbs 20:17

The sweet bread of success turned to gravel in their mouths though. Their popularity had them appearing all over US media and interviewers found their English very rough and suspicions arose over how their singing could be so good and speech so bad. They experienced technical difficulties during a live show where the vocal track got stuck and repeated the same line over and over. By the end of 1990, despite the US album jackets crediting the pair for the vocals, it came to light they were lip-syncing their songs and had never sung those songs themselves. Their Grammy was revoked and they fell just as quickly as they had risen.

People were upset about the fact they presented themselves as something they were not. The whole deception also met with legal ramifications. To put it simply, Milli Vanilli was a fraud. Of course, if they had billed themselves as what they were from the start, a lip-syncing European dance act, they probably wouldn’t have had anywhere near the same success, but they wouldn’t have been impostors.

Pulpit Syncing

No one thinks the music industry a bastion of morality and ethics, but even they have their limits. A fraud is a fraud, unless, of course, you can get away with it. Audiences have a certain expectation that the performance they paid for is a performance of the performers actually performing. When it turns out to be a fraud, they tend to get upset and feel cheated.

Lip-syncing as such is a form of plagiarism. In the real world, plagiarism gets singers, songwriters, and producers fired. Plagiarism gets reporters, journalists, and editors fired. Plagiarism gets authors and publishers fired. Plagiarism gets students and doctoral candidates fired. Plagiarism gets college and seminary professors fired. But, plagiarism gets preachers fed and maybe even promoted.

There have been a few famous cases in broader evangelicalism where plagiarizing preachers have been exposed, but they don’t usually end up fired. Even in small, conservative Baptist churches, where public visibility is near zero, preachers commit pulpit fraud by plagiarizing sermons more often than you think. Preachers lip-sync the sermons of other preachers to their congregations and the congregations are being defrauded. They’re actually being doubly cheated. They’re not hearing their pastor, whom they supply with daily bread, and they’re not hearing the preacher being plagiarized either.

There are numerous good articles on the subject of pulpit plagiarism and the wrongs of it in recent years, so I’m not going to add to that pile. Go forth and read what has been written. Rather, I want to deal with a problem on the opposite pole from plagiarism—originality.

Same Difference

Not a few pulpit Vanillis have their consciences pricked by decrying pulpit plagiarism and palliate said wounds by asserting the impossibility of originality. No one is truly original, they say, and so everybody plagiarizes. I suppose if we crowdfund the guilt it gets a bit thin by the time we get to the pulpit. This objection doesn’t argue that the charge is inaccurate, but rather asserts that everyone is guilty, and when everyone is guilty, no one is guilty. That logic is also a fraud, but let’s proceed.

Originality in the pulpit can be a problem when the preacher is so original that no one anywhere has ever seen what he sees and preaches. Such preachers have immunity from plagiarism because they are so legit original. No one has ever said what they’re saying. These preachers are like the Athenians that Paul encountered who continually pursued something new (Acts 17:21). Luke contrasts them with the Jews in Berea who thought Paul was preaching something new and so they “searched the scriptures daily,” to see “whether those things were so” (Acts 17:11). They found that while Paul was preaching things they had never heard, he wasn’t preaching anything new, in fact Paul himself defended his ministry by saying he preached “none other things than those which the prophets and Moses did say should come” (Acts 26:22).

Just because you or I haven’t heard something before, that doesn’t mean it’s new. But, if it’s some imaginative extrapolation from Scripture that the Scripture nowhere teaches, it is new and should be rejected. Bible preaching is supposed to be preaching of the Bible. Therefore, it’s not original or new. It’s timeless. Anyone with the Spirit and faith should be able to see it from the Bible. That holds true for supposedly sound preachers who always seem to find new paths to old truths.

Gateway Originality

Originality is something of a gateway drug for those who pursue it. A preacher dabbles with novel notions and the finding of types and symbols no one has seen, and ere long he is a fount of original ideas. Once you become that legit original, you’re too legit to quit, though quit is exactly what you should do.

50 Million Opportunities

But I say unto you, That every idle word that men shall speak, they shall give account thereof in the day of judgment.

~ Matthew 12:36

Spurgeon also managed do a few things outside the pulpit. He wrote over 140 other books besides his published sermons. He pastored a congregation of 4,000 members, edited a monthly magazine, and answered 500 letters per week. He read around six books each week, usually of substantial Puritan theology, and could remember what he read. He founded and oversaw over 60 organizations, had a pastor’s college that trained close to one thousand preachers in his lifetime, and he regularly counseled what he called difficult cases. In other words, all the hard situations no other pastors could figure out were referred to him. He had a wife who was near invalid and twin sons. He also lived with constant physical pain and criticism and slander. It’s estimated he donated nearly 50 million dollars to ministries in his lifetime. Even this is not everything that could be said about him. Oh, and he did it all without a Macbook or iPhone, or even electricity since the first public electricity generator wasn’t installed until 1881 in Surrey. For that matter, he did it all without a college or seminary education.

I know what you’re thinking. Nothing about that sounds average, and you’re right. It’s not average, and it’s one of the reasons it’s laughable whenever anyone compares a modern preacher to Spurgeon. Spurgeon has not been equaled, and the only safe or sane estimate is to expect that record to stand. But, in what way was Spurgeon average?

Average Numbers

I confess I am not a Spurgeon scholar, or any other kind of scholar while we’re on the subject of my deficiencies. I have read a lot of what Spurgeon wrote and a lot of what has been written about him. So far, I’ve only found one measure of Spurgeon where he was average, and that was his speech in the pulpit. I realize Spurgeon was famous for his unmatched eloquence in the pulpit, but I’m talking about his rate of speaking words in the pulpit. It has been figured to have been around 140 words per minute, which is within the average of 120-150 words per minute for public speaking. Spurgeon wasn’t a fast talker, neither literally nor figuratively. Here is one area where we preachers can take heart that we are very much like Spurgeon. We probably speak words in that same average range for public speaking like he did.

You might to be tempted to take small comfort in that fact, but we can make something of it. If Spurgeon preached 140 words per minute for an average of 40 minutes for the first three years of his ministry, he preached 3,360,000 words in those 600 sermons he preached. If he preached an average of ten times a week, then he annually preached 2,912,000 words. The average pastor today preaches 2-3 times per week. Let’s take the higher number and say the average pastor preaches three times a week for 45 minutes at a rate of 140 words per minute. Each sermon would be 6,300 words and add up to 982,800 words each year. That’s a lot of words, but still less than 34% of Spurgeon’s annual output. Even when Spurgeon was average at the number of words he produced per minute, he still managed preach three times the number of words preached by the average pastor in a year. Maybe he wasn’t so average after all.

Beyond the Numbers

Pastoring is, or should be, a long game. Most pastors would hope for 25-30 years of fruitful ministry. Some do get beyond that. 6,300 hundred words preached in a single sermon doesn’t seem like much. Of course, three sermons a week come out to 18,900, and 156 sermons a year add up to 982,800. The average pastor today is producing around one million words from the pulpit every year.

Those words really start to stack up when you count ministry in years. After 5 years of ministry, the average pastor has preached 4,914,000 words. 10 years doubles that number and 20 years quadruples it to 19,656,000 words. If you make it to 40 years, you will have preached 39,312,000 words, and 50 would be 49,140,000. Think about that. 50 years of preaching will produce around 50 million words preached. That is a lot of words. Of course, the average pastor in 50 years of preaching would still produce less than half the words of Spurgeon in his 38 years, which would be 110,656,000.

Let’s forget about Spurgeon for the moment and consider what these numbers might teach us. David and Moses both teach us the benefit of numbering our days ahead of time (Psalms 39:4; 90:12), so numbering our words ahead of time should benefit preachers. Considering the number of words we are likely to speak in public is especially sobering when we consider that we will have to account for each one (Matthew 12:36). Jesus said that every careless word will be accounted for and surely this will be a part of the accounting we all shall have to give in the future (Ecclesiastes 12:14; Romans 14:12; 1 Peter 4:5).

Every word a preacher speaks from the pulpit is an opportunity to get it right and get it wrong. We get it right when we accurately expound the text in its original contextual meaning and speak according to the analogy of the faith. We get it wrong when we misinterpret or misuse the text, but we also get it wrong when we speak carelessly. Careless words are spoken without thought and consideration.

Who’s Counting

I’m scared to think of how many of the millions of words I’ve preached to this point have been careless words. I know there have been wrong words in there, since I’m not infallible and don’t have all knowledge. I’ve been preaching for over 20 years. Do I have another 20 years to go? I don’t know. Only God knows that.

I do know that words from the pulpit will be judged with greater strictness than words spoken on the street (James 3:1). Since Jesus said every careless word would be accounted for, he’s obviously keeping count. How many preachers’ words are careless when they get in the pulpit with little preparation, study, and forethought? How many times do preachers just rare back and let ‘er fly? Will those words still be counted careless if they said what was true, but it was almost accidental because they gave it little to no consideration beforehand?

These thoughts should make us tremble over the words we have spoken and will yet speak. Each word matters and each word is an opportunity for right or wrong. The only way to assure we are preaching thoughtful and true words and minimizing careless ones is to follow the preaching program Paul charged Timothy with, “Preach the word” (2 Timothy 4:1-2). Paul meant “all scripture” (2 Timothy 3:16). Preach the words God gave in the way he gave them and you can make your words count for good.

A Portrait of the Preacher as an Everyman

Who are you? Are you an artist? Pastors get asked all kinds of questions. Just when you think you’ve heard it all, you haven’t. I was actually asked once if I was an artist. This question was a corker with no sort of warm up. I was caught by surprise but I didn’t need long to think about it. I am in fact not an artist. I can’t conceive of any possible description of an artist that would fit me. I have never even owned nor worn a beret. I did the only thing an honest man could do and admitted I was not an artist. Then I was told how the former beloved pastor, to whom I would never measure up, had painted this beautiful mural that really ought to be on display somewhere with other comparable works of true art. That wasn’t maybe the exact words I heard, but surely I’ve captured the sense of them.As a preacher, you will be compared to other preachers. People have some preacher or preachers in their minds who are the ideal preacher. Every preacher stands or falls to them in comparison to that ideal. Some men do have multiple talents and skills. They could build a house, paint a picture, sculpt like Michelangelo, pilot a Cessna, perform brain surgery, execute a deed of trust, and move an audience to tears while playing their own composition on the violin, all while preaching sermons like an angel come down from heaven. They seem to have won life’s lottery while you could wallpaper your whole house inside and out with your losing tickets. That is of course, if you could hang wallpaper, which you probably can’t.

As a young preacher, you feel a lot of pressure to measure up and to be like some such lofty ideal. Years into pastoring, you become depressed because you can’t see any great accomplishments stacking up. Any honest barber would tell you, “God makes the heads. I just cut the hair.” All any of us have to work with is what we have to work with. Honestly, most of us preachers are single talent preachers. We are not Charles Spurgeon, or anyone else other than ourselves. Remember the parable of the talents or minas. Each servant was judged by what they did with what they received and not by what someone else received.

If you work hard at the ministry, carefully handle the word of God so that you preach it accurately, and love your people, you have done your duty. So what that you’re not the most naturally talented guy in the ministry. I have heard some preachers who have loads of natural talent who don’t actually preach as well as some preachers without as much natural talent. That’s because they lean on that talent and don’t work as hard as they should at the study of scripture and the exposition of the text. They are regularly praised without doing all that work, but are they being truly faithful to their calling?

One day, we all will have to give an account of our ministry to Jesus Christ himself (1 Corinthians 3:5-15). On that day, you won’t be asked if you’re an artist like this other preacher was, or if you could tell jokes like old brother pastor did. You won’t be asked why you didn’t preach like this one or that one. You will be asked how you fed Christ’s sheep. That is our charge.

Saving Miss Piggy

It ain’t easy being green

“I wear rubber boots when it rains.” The kid to my right whispered in my ear. What should I do with that? I turned to the kid to my left and whispered to him, “I like to play in the mud when it rains.” My part was done. That kid turned to the kid to his left and relayed the message, and it kept going like that until the last one whispered to the teacher stationed at 12 o’clock. It’s called the gossip game and it was supposed to teach us some kind of lesson, but I guess it was lost on us. I remember playing a lot of group participation games like that in school.Around fourth grade, or maybe it was fifth grade, I had the opportunity of taking a creative writing class at a local college. The class was taught by one of the professors there. She went on to get elected to the state house of representatives, so I guess our class was a great success. One day she had us participate in a group brainstorming exercise. She started off with a word and then gave us prompts and we were supposed to respond with the first thing that came to mind.

She was teaching us about the need for conflict in stories and the goal of the exercise was to setup a problem and each of us would have to write a story to solve that problem. The memory tends to fuzz and fray after a few years, so I can’t recall all the details. We ended up with Miss Piggy as a character and she was in trouble. She might have been stuck up in a tree and we had to get her out of the tree in our compelling short stories.

Up a Tree

Our brainstorming session is also what is known as free association, which is a common technique used in improvisation workshops for the training of actors. It is also a psychology tool made famous by Freud. In free association you respond to a word or action with the first word or action that comes to mind. The goal is to get a free flow of ideas without any structure, logic, examination, or judgment of the value of the idea. At the beginning of class, we had no notion Miss Piggy would be stuck up in a tree, but free association put her there by the end.

Free association may have value, like the usefulness of hose clamp pliers for removing hose clamps, but is not equally applicable to all needs. I’m juberous of declaring value of free association for the pulpit and sermon making. Sometimes preachers are quite open about their free association process for developing a sermon. A preacher was driving and got stuck in a traffic jam and had an idea for a sermon on getting stuck in life. Maybe the traffic jam was due to a highway accident and he thought of a sermon on making a wreck of your life. A preacher was shopping at shops similar to those at https://www.shopfrontdesign.co.uk/shop-fronts/frameless/bristol/, which will definitely catch your eye. and passing all these signs advertising the best sale of the year, he got the idea for a sermon about not selling out.

At other times, preachers don’t take us along the development journey. He reads Luke 15:8-10, talks for a few minutes about the parable, and then announces he is going to preach on the thought: Have you lost your coin? Another preacher reads Mark 5:21-43 and says he will preach for a few minutes on this thought: How to get Jesus to come to your house. A preachers decides he wants to preach on the kingdom of God. The kingdom of God is a big subject with a lot of biblical information to work with, but the preacher starts associating. He thinks about what a kingdom is and what a kingdom needs. A kingdom needs a king, so he looks up some verses on kings. A kingdom needs subjects, so he looks up some verses. A kingdom needs laws, so he looks up some verses. A kingdom needs a throne, so he looks up some verses. He putters on along this line until his 45 minute quota is filled.

The Problem

A lot of preachers use this sort of free association exercise to develop their sermons. They setup the problem their sermon is going to solve. Sunday after Sunday they’re always saving Miss Piggy from the pulpit.

So, what’s wrong with preaching this way? Does free association or similar brainstorming have no place at all in developing sermons? The biggest problem with this approach to preaching is that saving Miss Piggy sermons are not text-driven, they’re idea driven. Rather than starting with the text of Scripture and asking, What has God said?, such sermons start with the free ideas of the preacher to setup a problem to solve that will more or less use some Bible verses. That’s just not preaching in any biblical sense of that term.

Preachers are called by God to preach his word and to work hard in his word and teaching (1 Timothy 5:17). The preacher’s primary job is not solving people’s problems, but preaching God’s book and giving them all his counsel (Acts 20:27; 2 Timothy 3:16-4:2). God’s word is inspired, inerrant, authoritative, and profitable. Your words are not. Your thoughts on how every Christian has an “Amen!” button are worthless in light of eternity. My thoughts on how to always have a smile will not save or sanctify anyone. Even sharing your personal journey is of limited value. Pastor Jason Shults wrote, “Your life story will only lead people to salvation to the extent that it points people to Jesus.”

Of course, preachers get ideas all the time from various circumstances, and I’m not saying there’s no value in them. However, if you have an idea for a sermon, there should be a biblical text that actually speaks to it without ripping it out of context and writing extra stuff in your Bible margins to make it fit. Otherwise, it’s not biblical preaching and you’re just saving Miss Piggy, and I guess that makes you Kermit. So the next time you’re up a tree trying to prepare a sermon, just look for Jesus to come by. It worked for Zacchaeus (Luke 19:1-10).

To Preach a Book: Analyzing

Preach the word; be instant in season, out of season; reprove, rebuke, exhort with all longsuffering and doctrine.

~ 2 Timothy 4:2

He pulled a VHS tape from the shelf and put it in the player. I can’t remember the name of the movie. I want to say it had the word “ninja” in it. It was a low budget action flick with a rice paper thin plot that was mostly an excuse to string together a bunch of martial arts fight scenes. I had seen some of the old, overdubbed Kung Fu pictures and always enjoyed the action. I don’t remember much about it, but I’m sure it was every bit as cheesy as it seems it would be.

We began watching, me for the first time and my friend for the nth time. He really liked the movie and had watched it over and over for who knows how long. Seeing it repeatedly had not dulled his enjoyment of it, but it had sharpened his perception of it. As it played, he added bits of commentary. Many of his comments were pointing out discontinuities in the film. At different points in the same scene there would be differences in the actors involved, costumes, props, etc. Of course, I hadn’t noticed it until he pointed it out.

I’m sure he hadn’t sat down with a clipboard and deliberately analyzed this straight to VHS movie. He had watched it so many times he began to notice these problems. I’m sure, after he had noticed a few, he began to look for them more consciously. While I wouldn’t recommend investing time in analyzing low budget actions flicks from the 80s, the act of repeated viewing, or reading in our case, is necessary to analyze any work.

Repetition

Before I am ready to begin working on a passage or a sermon, I have to analyze the book and identify aspects of it that will help me find the overall controlling theme. Repeated readings are necessary, but it helps if I have some idea of what I’m looking for.

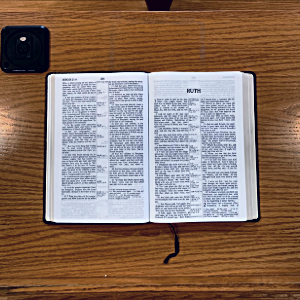

I chose the book of Ruth, so I immediately know the biblical genre of the book. It’s an Old Testament book and that means it is one of four main genres—law, history, poetry/wisdom, or prophets. Ruth is a book of history, but what kind of a book of history? I am ready to start reading.

On the first round of readings, I am not deliberately trying to notice anything. I want to read the whole book in one sitting, mainly to get a feel for the story. I may notice something or think of some questions in these readings. If so, I will write it down and go on reading. I’m not ready at this point to start researching and investigating. I first read Ruth in the KJV. I preach from the KJV and it is the translation I have predominantly used and am most familiar with.

I also read the book in other translations. Every reading helps me see the book as a whole. Different translations help me see it differently. The KJV was translated into very early modern English and uses archaic words and idioms. I sometimes assume I know what a word or expression means, when further study shows me I wasn’t right. I read the book of Ruth in the CJB, NASB, ESV, and NIV translations. I may like or dislike what a translation says. I may agree or not, but they are like first order commentaries on the text because they are what various scholars believe the original words to mean. I also read Robert Alter’s translation of Ruth in his collection titled, Strong As Death Is Love.

These readings were helpful in getting the big picture of the book in mind. I didn’t notice anything major among the translations that warranted further study. I’m likely to come across some translational issues as I do the deeper, line level study of the book, but I’m still not there yet. I am now ready for the next step.

Divisions

Earlier, I asked what kind of historical book Ruth is? Several readings confirmed that Ruth is one story and not a collection of stories, like Judges for instance. If I were classifying the book of Judges, I might call it episodic history. All the events in Ruth are connected and interdependent as one leads to the next from the beginning to the end, so Ruth is one story.

I am realizing as I try to describe my process, I am explaining some things I’ve never tried to explain to anyone before. I am using and going to use a bit of shop talk that I will try to explain. We should’ve learned much of this in high school literature class. Maybe we did, but have forgotten it. I may need to spend some time working on terms I use. There are various methods of literary analysis and I’ve noticed a number of terms that are inconsistent among different uses. I will try to explain the terms and the way I am using them as I go.

What do I mean when I say Ruth is a story? I am referring to the form of the book and not whether it is fiction or nonfiction. In Aristotle’s Poetics, he defined a story as a narrative that has beginning, middle, and end. He arrived at this conclusion from analyzing ancient stories to his day. He meant that a story is unified and cohesive, leading to a resolution. The beginning starts the story, giving an opening image that gets out of balance in some way and leads to the middle. The middle continues the story as resolution of the imbalance is sought and leads to the end. The end is the resolution where the imbalance is overcome and the closing image of the story is typically a reverse, or mirror image of the opening. Ruth definitely fits this description.

At this point, I need to start dividing up the text of the book. I am not referring to preaching units at this point. I am analyzing the story, so I want to divide the book into the different scenes of the story. A scene is a smaller unit of the larger story. Just as the whole story has beginning, middle, and end, scenes also have beginning, middle, and end. A scene has an opening image and inciting action that causes change leading to a resolution of the scene. I am looking for the smallest unit of the story, which satisfies that description.

I started this process for Ruth by taking the Word document of the AV text of the book and removing all chapter numbers, verse numbers, and spacing. I ended up with a document of the text of the whole book that looks like one long paragraph. You can find that file here. I printed the file on a single sheet of 11×17 paper. In this case, the book is short and I could fit the entire text on the front of an 11×17 sheet.

I took that sheet and read the text over and over and over again. I don’t know how many times, but it was certainly several times. I read and looked for scenes and began marking the text up to identify the scenes and the components that made up the scenes. Here is what that sheet looked like when I was done. You can click on the thumbnail to enlarge it.

I identified six scenes that satisfied the beginning, middle, and end form of story. You will notice the marks and notes I put on that sheet. I will explain those later, but for now I want to talk about finding the controlling theme. During this process, I identified the controlling theme as finding rest, and noted that in the upper right hand margin. I circled the word rest twice in the text. It actually occurs a third time, but I didn’t realize the significance of that third occurrence until later.

In the AV text, the word rest occurs three times (Ruth 1:9; 3:1, 18). Each time, the Hebrew word is different. The two main occurrences (Ruth 1:9; 3:1) capture the concept of rest as what is found in the home of a husband—love, peace, security, abundance of provision, continuing life through children and grandchildren, etc. The ideal of rest is present throughout the entire book and works on the different levels of want and need for the main characters. I will explain more about that later.

I have a lot to work with as I move forward in studying the book. I don’t consider my initial decisions to be final. They will need to be tested and refined as I continue to work through the book. I realize I could open up commentaries and other books on Ruth and get all this already broken down for me. At this point in the study, I haven’t opened any of those books and it will be a while before I am ready for them. First, I need to know what I think and understand about the book before I ever hear what others think about it. Second, you will notice when you read some different commentaries and books that they don’t all agree on how to break a book down or even on what the primary message of the book is. I will refer to other books as a check on my work later, but I’m not ready for that at this point.

Up Next

In the next post, I will write more about the scenes and how I divided those up.

This post is part a of series. To read the entire series from the beginning, go here.